The Super Basic Basics

Table of Contents

Some Notes

As we go through these things, I’ll explain them in a lighthearted manner that will hopefully be easy to understand. I think one of the most important ways for an average person like me to be successful at easing into machine learning is to be “blissfully ignorant”. That means don’t try to understand more than you can for now. You’ll end up in a never ending reading cycle of death. Think of learning ML as untying a tangled ball of string. Start by getting your fingers in there and shaking it like a mad person. Then when you get to the end and you see some stubborn knots, you can begin to work through those. Without further ado, we begin. :)

Some Simplified Explanations and Examples

Machine Learning (ML)

A super vague, general term that is simply the noun describing the act of teaching a computer how to do things. However, more specifically, we now almost always refer to ML as a way to teach a computer how to do things that humans are good at (i.e. recognize images, understand speech, predict trends, traverse mazes, drive cars, beat games, etc.).

Reinforcement Learning (RL)

Imagine you’re trying to train a blind man to accomplish some task. To do this, you decide the man needs to have some pieces of information: one, some kind of sensory input for the dude to learn what he’s doing, what’s going on around him, and/or where he is, and two, some kind of feedback about whether he’s doing well or not. This type of training is what we call reinforcement learning or RL. In more “official” or “science-y” terms we can say that we use RL to teach an agent how to accomplish or optimize an objective function by giving the agent some sensory input or state and some feedback about its performance a.k.a. reward.

States and Actions

Signified by . Imagine yourself trying to walk through a field to get somewhere. There are two things you need to do to avoid being a vegetable. One, have some knowledge of what’s going on around you (ex. location of my goal and what’s 3 steps in front, behind, left, and right of me). That’s your state. Two, you need to actually do stuff to get there (ex. move forward, back, left, or right). That’s your action.

Trajectory

A trajectory is simply the path you take to try to get to your goal. I also call this a series of “state-action pairs”, which simply means your trajectory develops as each time you decide you want to take an action, you evaluate your state and then take an action (See, it’s so easy a caveman could do it. Rest in peace old GEICO commercials).

Policy

The thing our RL agent uses to choose what actions to take. For example, a random policy for the field example would be, given some state (ex. everything is clear in back, left, and right, but there is a tree in front of you), take a random action (ex. 25% chance to smash face first into the tree, 25% to move in each of the other directions). Clearly this random walk example is, too put it nicely, “naive”.

Neural Network

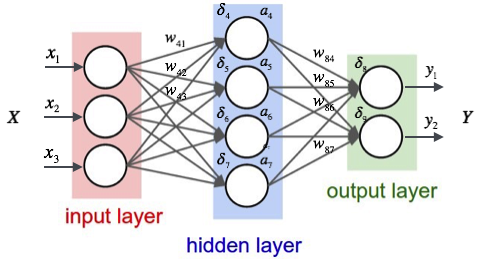

Every policy is a function. It takes in the state of things and spits out an action. The neural network is just an example of one kind of policy function (it can also be used as an approximator for any function (e.g. q-value, value function, etc.), but for simplicity, let’s only consider what we understand for now, which are policies). On one side (the left side in these fancy pictures), you feed in the state, which is usually represented as a 1D or 2D arrays (a list of numbers, or a list of same sized lists). On the other side (the right side in these fancy pictures), we get out our action. Each network is composed of a jumble of numbers called “weights”. The simplest versions of these networks just multiply the input array by the network’s weights using matrix multiplication to get the output. That’s what those “w”’s represent.

Discrete vs. Continuous

Think of what you see when you look at letter on your computer screen. Let’s take this “O” for example. Looks curved doesn’t it? That’s an example of what we mean by continuous. You can make infinitesimally small movements to created curved shapes. However, if you zoom REALLY far in, you can see the edges are pixellated. This is means that there isn’t a good way for a computer to be able to visualize such infinitesimally small changes so it uses rigid, finite, squares to approximate them. That’s what discretization is, simply making continuous things finite.

Diving Deeper

This whole point of this section is to answer two questions:

- What are us scientists trying to do?

- Why is it hard to solve?

State

So we know the state is the information you have each time you want to take an action step. When designing algorithms, scientists try their best to give the agent the “optimal state”. What is that you ask? The optimal state is one that is minimal, but complete. What does that mean? Well, if you didn’t know, ML algorithms can take a crazy amount of time to learn, even with the insanely fast computing hardware companies are throwing around these days (ex. It took 4-6 weeks to train Alpha Go). So, the more information you give an agent, the longer it takes for it to learn a decent strategy. Also, if your policy function used to translate states to actions isn’t designed to handle all the intricate relationships between various parts of the state, then, even with infinite training time, your algorithm will inevitably cap out at some sub-optimal performance (if it even learns at all). Yikes.

Neural Networks

- A simple way to think about what the weights are is to think of what parameterizes a function. In the linear case, a function is described as . Since is your input and is your output, these are equivalent to our state and action respectively. Now the things that are left, and , are our weights (the term has a special name called a bias, but ignore that for now. Don’t worry it’ll come back later :)). The key is that by changing and , we can arbitrarily affect how our state maps to our action. Now, that was just a simple linear example. In reality you can have way more than an and a . You could have the whole darn alphabet and more if you wanted (even worse you can have multiple dimensions… :o oooh. But yeah, we’re going to shut down that thread right now before your brain explodes). The whole point of neural networks is that by doing various multiplications and additions on our inputs, we can theoretically approximate any real policy function.

- The difficulty is that every system has an exact function that will map each state to its optimal action so there is an optimal setting for our weights, however we don’t know that exact function, so we have to use an educated “guess, check, and update” loop to keep improving our guesses for what our weights are. We don’t even know if our neural network has too many or too little weights or even if the connections are hooked up properly, so, researchers have to make educated guesses as to which architectures they will use for specific problems.

Policy

- Here we are, back to the good ol’ policy. As you saw from my cute little “randomly walking through a field” example up top, of course we want to do better than random. However, this toy example is actually harder than you think. Let’s start out with the human way of thinking and see why this is a deep unforgiving rabbit hole of a problem. Take a deep breath. This is about to get wild.

- “Dude, if you see something in your path just move out of the way”

- Okay… few problems here. Which way do you go? You’re probably thinking the most logical thing which is “out of the options of front, back, left, right, move in the direction that is clear and moves you closer to the goal”. Okay, let me give you a counter example. Say you expand your state a bit. Now you can see the birds eye view of the entire field… and realize it’s a goddamn maze with dead ends and all sorts of dangerous obstacles just waiting to destroy you. Now let’s revisit the problem “which way do you go?”. This is now back to the issue of state that I outlined above, how much information should I give the agent and what can the agent solve using exploration and what does it need to know via sensing? A simple example of the difference between the two is that if you had a static maze, you could map out your surroundings by building knowledge by exploring your environment and building a global understanding which states are good and bad (this would be considered model-free). However, you need to at least sense your immediate surroundings to make sure you know where you are locally and to be able to adjust to moving obstacles. So, think simple question of “which way do you go?” leads to a ton more issues: “what’s going to happen in the future?”, “what impact does my trajectory history have on my current decisions?”, “can I even do any better given the information I know?”, “how much should I care more about my immediate benefits vs my future benefits and how does this ratio impact my decisions?”. The list goes on and on.

- Next: “Your example is too simple. I don’t live in a grid world. I want to be able to move and turn in a continuous manner. How does that work?”

- This is a methodology issue. There isn’t a very good answer to this one. You could either discretize your states and actions or you could using something like policy gradients

- “Dude, if you see something in your path just move out of the way”